![]()

Manish Chandra is a small-time hotelier. He runs two hotels with 17 rooms. He addresses all the pre-booking calls himself — at times up to 50 calls a day. He may be small-time, but he is not a garden lodge operator catering to backpackers. For starters, Chandra’s properties are deep in Uttarakhand, one overlooks the majestic Himalayan range, and the other is by the serene Kalsa river.

Such views don’t come cheap. A room per night ranges between Rs 8,000 and Rs 12,000 (plus taxes) in peak season; that’s as much as, or even more than, what some luxury hotels in the Capital would ask. Chandra is not bending over backwards to woo consumers either; at times he politely declines a booking if he thinks the guest(s) may prove a misfit.

One more thing: Chandra insists he isn’t doing this for money. After a globetrotting career with MNCs, successful entrepreneurial stints with private equity and corporate finance, he has enough of the dosh. “The biggest luxury is to have the time and the freedom to approach life whimsically. I have it,” he says.

In Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, self-actualisation is the ultimate stage of human motivation where “what a man can be, he must be”. Chandra may well be there. And he isn’t alone. A slew of high-flying, successful executives with the financial cushion and the conviction to get off the corporate treadmill are living the life they once dreamt about.

Gaurav Jain of Aamod Resort says just the sheer joy of creating a unique experience for his guests gives him a high that no salary or job can give. LaRiSa’s Priya Thakur says going back to her roots in Manali and setting up a boutique hotel with a compelling experience satiates her ambition in a way no corporate job would have. Passionate about their new innings, most of these boutique hoteliers are hands-on, and are shunning the structures and processes that large hotel chains have to standardise experience.

It helps that these entrepreneurs are tagging on to a hot global trend in the hospitality industry. Boutique hotels are typically small, upscale, aspirational hotels (10-100 rooms) that have unique settings and offer personalised services.

Globally, they are growing rapidly. So strong is the trend that even big hotel chains are embracing it. Marriott has partnered with boutique hotel “inventor” Ian Schrager to launch the Edition Hotels worldwide, including in India. The hotels offer a unique and individualised experience. Similarly, Sofitel Luxury Hotel launched Sofitel So in 2010. Hyatt has a brand called Andaz, InterContinental Hotels has Hotel Indigo and Wyndham Hotel Group has Tryp by Wyndham.

Three important developments are amplifying the popularity of boutique hotels. Well-heeled travellers who have been there and done that are looking beyond standard five-star luxury for unique experiences in less predictable places to make their stays more memorable.

Further, in a social media-driven world, people are constantly broadcasting their holiday experiences. Their efforts are equally matched by likes and comments on their social networks. “The more unique the experience, the more people want to share,” says Nikhil Ganju, country manager (India), TripAdvisor, an online travel firm with interactive travel forums. As a result, both the need and the desire to seek non-homogenised, authentic and unique experiences have been rising sharply. Small boutique hotels have the nimbleness and willingness to cater to this trend. Take the example of Aamod Resorts.

For a couple celebrating their anniversary, it could put together a special evening with a couple’s spa under the sky, followed by a dinner, privacy ensured. It is an experience no money can get you in big hotels, says Jain of Aamod Resorts. There is another reason why boutique hotels are becoming a rage. Technology is disrupting the business. Travel bookings have significantly moved online. While small boutique hotels may not have the big banner brand with certain guaranteed service standards, travellers’ reviews on websites come handy in vetting small boutique hotels and their services. “With technology, online search and booking, discoverability of boutique hotels has become a lot easier and cheaper,” says Ganju.

Here are five entrepreneurs, who have shunned their well-paying corporate jobs to chase their boutique hotel dreams:

Meet Me at Manali

For Priya Thakur, the hospitality blueprint took shape about three years ago. She was in Manali, her parental home, and chatting with her dad about hotels mushrooming all around. Born and brought up in Himachal Pradesh and chasing a corporate career in Mumbai, Thakur always yearned to retire to her roots. “Living in big cities, with a hectic job, and doing the same mundane stuff on a daily basis wasn’t exciting anymore,” she says.

For Priya Thakur, the hospitality blueprint took shape about three years ago. She was in Manali, her parental home, and chatting with her dad about hotels mushrooming all around. Born and brought up in Himachal Pradesh and chasing a corporate career in Mumbai, Thakur always yearned to retire to her roots. “Living in big cities, with a hectic job, and doing the same mundane stuff on a daily basis wasn’t exciting anymore,” she says.

It was then that the idea of a boutique resort emerged. The decision was a lot easier because the Thakurs owned a 20-acre apple orchard on the outskirts of Manali. Soon the mother of a 13-year-old daughter quit her corporate job with PVR Cinemas to build a resort with her brother Puneet.

With no background in the hotel industry, and the prospect of competing with some 500 hotels in Manali, the Thakurs grappled with the business model — should they build a highrise mass commercial hotel or a smaller boutique hotel for premium travellers? They eventually chose the latter, building a 22-room resort that is inspired by local architecture. Located in an apple orchard, LaRiSa has chalets/cottages that offer a 360-degree view of the mountains. Guests can dine under the stars, have a barbecue dinner, go trout-fishing or pluck their own vegetables and strawberries from the organic garden. Thakur takes care of sales and marketing and her brother the day-to-day operations.

The project has been full of challenges. Hiring and training staff locally was one of the biggest. The Thakurs have opted to hire locally; more than their knowledge of the English language, they were looking for politeness, courteousness and the ability to deal with guests.

Sales and marketing was an equally big challenge in a sector dominated by travel agents who, as Thakur points out, tend to “push those properties where they get a higher commission”. So she leaned heavily on social media and word-of-mouth. It may be working. This summer, its second year of operations, LaRiSa’s occupancy is 80%. How viable is the business? “For the first few years, you do not make money. I am totally okay with that as long as I can sustain (the operation),” says Thakur, who is eyeing a breakeven in operations in four years.

The Great Grad Dream

In 2008, Gaurav Jain and his wife Kanchan returned to India after working overseas for over a decade. “We wanted to give shape to our college dream,” he says. Gaurav and Kanchan, while they were classmates at IIM-Calcutta, had worked on a project to set up a resort in Himachal Pradesh. Both quit their cushy jobs and deployed their savings to turn entrepreneurs. But Kanchan has now gone back to her job in the financial sector. “It helps cushion the risk,” he says.

Today, Jain’s Aamod Resort runs 10 boutique hotels, ranging from sixto 43-room properties in Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Goa and Rajasthan. They will soon go international with one in Sri Lanka. The properties are all small — between half an acre to 8 acres — have plenty of green cover and a thrust on personalised services. They try and surprise their guests by serving meals at different locations within the resort.

To keep the capital expenditure low, Jain has pursued an asset-light model, in which he leases properties instead of buying land or hotels. He is also looking at a franchise model where the real estate is owned by someone else and Aamod manages the brand and service. This model, he says, typically allows him to break even between the third and fourth year of operations.

The journey hasn’t been easy. “I made all the mistakes in this business that I would advise my clients not to make when I was a consultant,” he grins. From cost and time overruns to biting more than one could chew and not fully factoring in the downsides, problems were aplenty. For example, in 2009, he signed three lease deals to start three hotels a year later. He could start only one, in Shoghi, a suburb of Shimla, on time. “These things happen when passion and commerce get mixed up,” shrugs Jain.

The Jains put their entire savings at risk by not tapping into investors. The advantage of that, of course, was that they could pursue the business model they believed in, without having to worry about bottom line compulsions. “If I had made it a boxlike, three-star hotel, it would have been much more profitable. But there would have been no creative challenge in doing that,” he says. As he looks back, Jain admits that he misses the financial security and certainty of a job, and the peer group at work even more. What he doesn’t miss, however, is office politics. “While financial constraints are considerable, the freedom of decision-making and joy of creating something new are unparalleled.”

Sophisticated Leisure

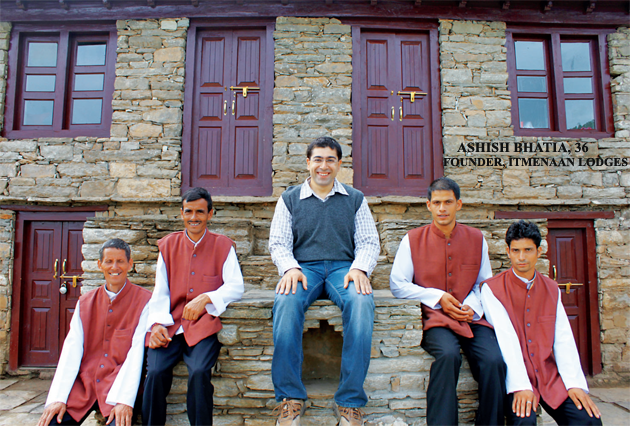

Ashish Bhatia loves to travel, one reason why the IIT-IIM graduate took up a consulting job. “I would travel four days a week, spending time at clients’ sites and exploring new places,” he says. When he returned to India from London, with his family, around 2008, buying a holiday home on the hills was on top of his to-do list. It helped that his wife had a stable teaching job at IIT-Delhi. In 2009, Bhatia decided to take a break from his high-flying career and travel for 15 weeks, soaking in nature. The next step? Use up his savings to build a summer home. He found a suitable property in the Kumaon region in Uttarakhand — a 100-year-old cottage, with four rooms, sitting on 10 acres. The Bhatias renovated it, added one more cottage, a lounge and a restaurant. “We started it not because we saw it as a great business but because it was something that I was passionate about. I didn’t do too much of cost-benefit analysis,” Bhatia says.

Apart from his savings, Bhatia relied on friends and family for funds. He needed all of it and more. It took him eight months to renovate the property — something he had budgeted to complete in half the time. “I finished all my money,” he recalls. So he was forced to take up part-time consulting assignments. There were other problems, too. Just two of them: getting workers and building material in the hills. So much so that when he got his first booking for October 2011, plumbers were at work, which went on till September. One day, Bhatia slumped into a chair in the patio, stared at the Himalayas and wondered whether building a resort was a good idea. “Suddenly, a butterfly came and sat on my hand,” he recalls. That was the turning point. “Just for that moment, everything suddenly felt worth it,” he says.

It surely has been since then. Targeting wellheeled, evolved travellers, Itmenaan Lodges has three properties now — in Almora, Amritsar and Bhimtal. Bhatia says the thrust is in offering personalised service and an exclusive experience amid nature for the sophisticated traveller. As for money, the company just about breaks even and from this year will make a small profit. What does he miss about his corporate job? “The expense account, free miles and hotel points,” he grins. As for the lessons, he’s learnt a hard one about money. “I invested all my savings and one day I realised that my account was empty and I had taken loans on my credit cards.” He advises that one should always plan expenditure with a significant buffer. “Thankfully, my wife works and her support helped me during the tough period.”

The Village Head

In 1991, while chasing a corporate career, advertising executive CB Ramkumar bought 12 acres of farm land on the outskirts of Bengaluru. “It was for my father-in-law who had just had a cardiac issue. The farm land was to keep him busy,” he says. As planned, the father-in-law began to potter around the farm and plant trees. They were growing a range of things, from fruits and flowers to herbs and vegetables. Ramkumar, who was working overseas then, would make two trips every year and do his bit on the farm. Later, as they were planning to build a farmhouse, his father-in-law fell seriously ill and stopped farming.

Soon after, he passed away. “We were proud owners of a lovely farm but we were neck-deep in debt,” he recalls. Ramkumar’s first plan was to hire a manager to run the place commercially. But friends and family, who were invested in the land, preferred Ramkumar to take charge of the project. In 2003-04, on a whim, the Ramkumars decided to pack their bags and move from Dubai to Bengaluru.

“I have always made decisions on impulse. My wife thinks I am nuts,” he says. For instance, he says, he once decided, virtually overnight, to do a cycle tour in Lebanon to raise money for a charity. Another time he decided to cycle from Kashmir to Kanyakumari. The plan wasn’t to build a hotel. “We wanted to build our house and build six little tents where people could come and stay,” he says. This was to be their dream home. His wife had always romanticised about a village where they could live and retire.

The project evolved into a 100% eco-resort, Our Native Village, where sustainable technologies and principles have been deployed for most of their needs: energy, water, waste management and food. “Our resort is self-sufficient. From power to waste management, we do not need anything from the government,” he says. From a guest point of view, they are trying to replicate the experience of village living. From having wall murals to reviving interests in Veera Kallus (hero stones) and village games, they “deliver a simple Indian village experience,” he says.

The risk, for the Ramkumars, wasn’t as huge as it is for most people who chuck a job to chase their dream. “I was fully convinced of the idea of a 100% eco-resort,” he says. Over eight years, he learnt about sustainable living and farming. The toughest moment was accepting the reality that his passion was of no value unless it was commercially viable. For now, he has both — his passion as well as a modest profit.

Soul Satisfaction

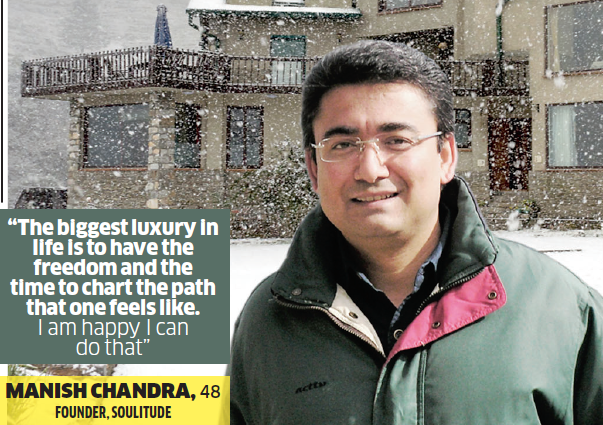

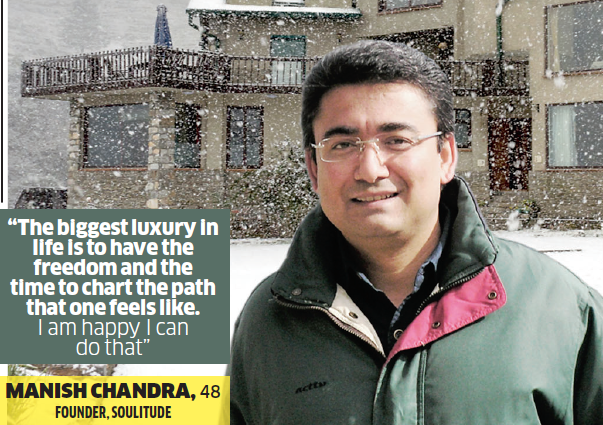

By any yardstick, Manish Chandra has had an impressive career track. The chartered accountant worked with the global Big 4 accounting firms, did stints in the UK and worked with a range of MNCs, from Nokia to HSBC. In 2000, he stepped off the corporate treadmill to turn entrepreneur. Over the next decade, he first started a travel portal Net2Travel.com, which was sold to Rupert Murdoch-founded News Corp, and then moved on to dabble in private equity and corporate finance.

By 2010, Chandra was having a mid-life crisis. “I wanted a work-life balance and didn’t want to work for money. We aren’t very materialistic people,” he says. His wife used to run an NGO called Little Souls, which made teaching modules to instil values in young children. It was then that he decided to convert his vacation homes into boutique hotels. A Delhi boy, Chandra always had fond memories of summer holidays in the hills. Around 2000, he had bought land near Ramgarh in Uttarakhand to build his holiday home.

“I was at it like a mad man. I would work weekdays in Delhi and on Friday night head to the hills to supervise work,” he recalls. Around 2005, when his neighbour, a builder, started constructing holiday cottages to sell, he promptly bought him out. He didn’t want a tourist rush to unsettle the quiet of the place. Soon he had 10 rooms, far more than his small family could use. They started inviting friends and relatives. “Almost unplanned, our private home evolved into a boutique hotel,” says Chandra.

He now has two properties, Soulitude in the Himalayas and Soulitude by the Riverside. Targeted at the well-heeled looking to get away from the hurly-burly of city life, his holiday home, Chandra says, is ideal for those looking to slow down, rejuvenate and simply be.

“It’s a vacation home, not a hotel or a resort,” says Chandra. He shuns standard structures and processes that hotels deploy; instead he pushes for personalised service that exudes the warmth and comfort of a home. Every customer call is handled by Chandra personally. “It is important for me as it helps me understand our guests and their needs better. There are times I feel our place may not be right for their needs and I direct them elsewhere,” he says.

Over 30% of his guests are repeat visitors. The properties have high occupancy this summer. “Operationally, we break even. And I am okay with that as I am financially comfortable,” he says. Chandra may not be making money hand over fist but non-monetary returns have been substantial. “I used to be a typically aggressive corporate guy. I have now become a lot calmer and at peace with myself,” he says.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Click here to read the original post on The Economic Times website